Learn why hybridity is the key to tackling today’s most ambiguous business challenges.

When A.G. Lafley was named CEO of Procter & Gamble during the summer of 2000, the task of turning the organization around looked overwhelming. The price of a share in the consumer packaged goods giant had declined by nearly 55% in just two months. The company was missing revenue and profit targets as it learned to grapple with the Internet and new global competitors.

To remain the world’s preeminent maker of useful stuff for the house, P&G needed to make a lot of changes very quickly. Lafley saw design as being central to P&G’s transformation. Design promised to unleash the creativity of the organization and find new ways to unlock value that a marketing-driven company might not have discovered. To lead the charge, Lafley appointed Claudia Kotchka as the company’s first-ever VP for design strategy and innovation in 2002. Her job was remarkably ambitious: Make innovation happen at P&G.

And she did. In her nine years in the role, Claudia up-ended the status quo in P&G’s product development process. She placed designers within the company’s many business units so they could shape strategy directly instead of just designing how products looked. She educated business people in the company about the strategic impact design could have. She formed a board of leading external design experts who offered guidance for how to make P&G into a world-class design organization.

P&G Growth

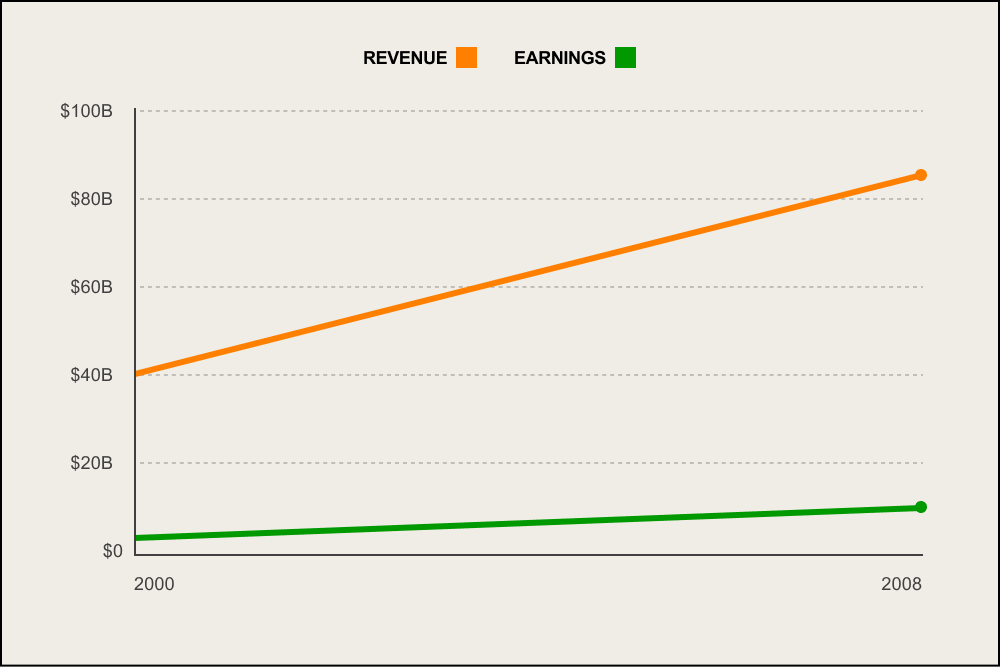

Over time, her efforts have P&G to once again become one of the most innovative companies on earth. Between 2000 and 2008, revenue more than doubled from $40 billion to $83 billion, while earnings took a gigantic leap from $2.5 billion to more than $12 billion.

This growth is the kind of performance one expects from an IT company or a firm operating in an emerging market. Not a 200-year-old soap company based in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Hybrid Thinking

Download

Claudia’s success has been celebrated in many corners as a triumph of design thinking. Though its definition varies depending on who you ask, most of its proponents (including many at P&G) agree that design thinking is any process that applies the methods of industrial designers to problems beyond how a product should look.

My mentor at Stanford, Rolf Faste, did more than anyone to define the term and express the unique role that designers could play in making pretty much everything. Not just products, but services, experiences, and presumably finance, education, and government, as well.

By this standard, what Claudia achieved at P&G is perhaps the most impressive accomplishment of design thinking’s relatively recent heritage. She took what she knew about design and applied it to a broad array of problems faced by one of the world’s largest corporations. On the face of it, Claudia’s tenure at P&G is a testament to the power of thinking like a designer.

Hybrid Thinking

Here’s the problem: Claudia Kotchka isn’t a designer. She’s an accountant by training. And she spent most of her career working in marketing. It would be hard to envision a business executive with a more traditional background. While Claudia’s success makes a great case study for the triumph of a designer finally being brought into the conversation, it’s just not true. And it calls into question whether design thinking is really the missing ingredient in innovation.

Indeed, the real power of Claudia’s story is that she isn’t a designer. I see this phenomenon all the time: accounts who lead a design revolution, former journalists who manage a technology lab, even doctors who become agents of organizational change. All of these cases suggest that something bigger is going on, more powerful than the adoption of a single school of thought. The secret isn’t design thinking, it’s “hybrid thinking”: the conscious blending of different fields of thought to discover and develop opportunities that were previously unseen by the status quo.

Claudia’s lack of experience as a designer didn’t make her a weaker proponent of design, it made her a stronger one. She immersed herself in design thinking and then merged it with her experiences in accountant thinking, marketing thinking, and several more besides. To walk away concluding that design thinking is what makes P&G great would be like going to the movies and concluding that Indiana Jones is a great hero because he always wears a hat.

Hybridity matters now because the problems companies need to solve are simply too complex for any one skillset to tackle. We’re in an era when car companies are trying to grapple with massive changes in technological capability and market need, when cell phone companies are trying to own global entertainment, and when snack food companies face extinction unless they figure out how to promote health and wellness. As Lou Lenzi, a design executive at Audiovox, once told me, if you want to innovate, “You need to be one part humanist, one part technologist, and one part capitalist.”

Hybrid thinking is much more than gathering together a multidisciplinary team. Hybrid thinking is about multidisciplinary people.

John Lasseter, the co-founder of Pixar and creator of Toy Story, isn’t beloved and admired because he’s good at technology. We love him because he effortlessly fuses technology, art, and storytelling.

Alton Brown, star of Good Eats, began as a TV producer, then decided to learn how to cook and became fascinated by food science in the process. His program on Food Network is a potent admixture of cooking show, science class, and sketch comedy, wrapped into one of the slickest how-to shows on TV.

It’s particularly interesting to note how many proponents of design thinking are actually hybrid thinkers themselves. David Kelley, the celebrated founder of the design firm IDEO, has a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Carnegie Mellon in addition to his master’s in design from Stanford.

My own personal experience is that hybrid thinkers make for a much more interesting day at work. At Jump Associates our staff includes a former partner at Deloitte who’s also an award-winning sculptor. We’ve employed a Ph.D. in cognitive science who’s also a filmmaker. And another one of my colleagues has an MBA as well as degrees in Chinese language and international relations.

Jump is constantly on the hunt for hybrid thinkers, folks who can connect the dots between what’s culturally desirable, technically feasible, and viable from a business point of view. And to be sure, it hasn’t made our recruiters’ lives any easier. We live in a society that prizes depth in a single field of research over breadth in multiple areas. Innovation, however, demands that you see the world through multiple lenses at the same time, and draw meaning from seemingly disparate points of data.

Without a doubt, design thinking is an important new body of knowledge for companies seeking to expand their capacity to innovate. But the goal isn’t to shift from one mindset to another. Learning new ways to think isn’t very helpful if you forget what already know.

Dev Patnaik

Dev Patnaik