The nationally ranked Stanford Children’s, is one of the only hospitals exclusively dedicated to pediatric and obstetric care. But their award-winning standard of care wasn’t always a given. By taking a future focused approach, they reinvented the complex care delivery model, changing lives while shaping the future of healthcare.

Nationally ranked and internationally recognized, Stanford Children’s is the only healthcare system in Northern California — and one of the few in the country — exclusively dedicated to pediatric and obstetric care. Every year thousands of children and their families travel to Stanford Children’s to seek world-renowned treatments. In 2020, it was named one of the Most Innovative Children’s Hospitals by PARENTS Magazine for its cutting-edge medical advancements and programs. Today, as the healthcare ecosystem continues to evolve, Stanford Children’s is shaping its future.

Future Focused- Stanford Children’s Story

Download, save, share

Stanford Children’s is particularly well known for its industry-leading expertise in caring for children with complex medical needs. While growing up, a typically healthy kid might land in a children’s hospital once or twice. Maybe it’s because of a broken arm or leg. They get patched up, go home, and never look back. But kids with complex medical conditions have an entirely different experience. They regularly see 15 different specialists. And it’s not because they get “sick” a lot. It’s because that’s just what it takes to manage their conditions. They’re not going to be “cured.” They’re patients for life. Today, through Stanford Health’s dedicated program, these children become healthier, stay out of the hospital more, and live the life of a kid.

But that standard of care wasn’t always standard. In fact, in the early 2000s, it was quite the opposite. As the Stanford hospital system formed specialty partnerships with other hospitals, the patient experience suffered, costs soared, and frustrations rose, especially for complex care patients and their families. That patient experience was so clustered that the problem even reached the accreditation board. When it did, the leadership team at Stanford Children’s sprung into action. Through a series of future focused initiatives, the team grounded in new insights about multiple stakeholders, challenged their assumptions about what’s possible, and set out to build the best care delivery model yet. What followed quickly proved what was previously thought impossible in the healthcare system – they built a program that simultaneously improves patient outcomes, enhances the patient/family experience, and reduces expensive healthcare encounters.

A Bigger, But Not Better Health System

Largely in response to managed care, the U.S. hospital industry consolidated substantially during the early 2000s. At the time, many inside the healthcare industry saw consolidation as a path to providing higher-quality care and other benefits for consumers. That proved to not be the case.

For its part, Stanford Children’s entered joint ventures with several community-based hospitals. Rapidly, what was once a single hospital-centric campus became a collection of nearly a dozen pediatric specialty centers throughout the Northern California marketplace. While the resulting system was now exceptional at treating children with complex medical conditions, care management and delivery had become duplicative, frustrating for patients, and costly for the organization.

Then CEO and President Christopher Dawes noted that the children’s hospital and health system were “like the United Nations. There was no consistency. Everyone was speaking a different language.” Patients and families were left struggling to navigate a complex medical system with little support from the hospital.

A letter to The Joint Commission, the authority on healthcare accreditation, brought Stanford’s patient experience failures to the forefront. Penned by parents dealing with the highest levels of medical need for their children, it painted a scathing assessment of the hospital’s care management model. “Parental and family needs are secondary to the whims of scheduling staff and doctors,” they wrote. “We have come to expect this failure to communicate among your specialties.”

How bad was it? Just imagine what it was like for Amy* and her family. At the time, Amy was admitted to the hospital 20 times during one 18-month period, staying for about two weeks a stretch. Each time, the medical team at Stanford Children’s Health saved her life. But at what cost? Enduring regular emergency trips to the hospital was no way for a child to grow up. It wasn’t an effective use of the hospital’s resources, either.

Coordinating care for children with medically complex illnesses was critical in providing a better patient experience and improving lives. But it was also important for managing costs. Children with medical complexities occupy an increasing number of beds in pediatric hospitals. Nationally they have more adverse healthcare events, higher readmission rates, and longer lengths of stay. They account for 1 percent of all children, but as much as 30 percent of total pediatric healthcare costs. As Stanford’s system got bigger, so did the costs and the complexities of delivering quality care.

A New Approach to a Seemingly Unsolvable Problem: Improving Outcomes While Lowering Costs

Administrators recognized the urgency of the situation. It was clear that patients and their families deserved more than a literal lifesaver in a crisis. They deserved an equally stellar patient experience. And as for the hospital, they couldn’t afford the costs associated with uncoordinated, duplicative care.

The team faced a highly ambiguous and seemingly intractable problem – how to develop a delivery model that simultaneously lowered costs, enhanced the family experience, and improved patient outcomes. In the hospital world, it’s been said patients might get one or two of those, but not all three. Organizational leaders sensed they couldn’t rely on traditional strategic models to solve their problem. If they wanted to create something new, they had to find a future focused partner, rather than rely on the industry advisors they were used to. They turned to Jump for its insight-driven approach and expertise in solving seemingly unsolvable problems with multiple stakeholders.

The process enabled the Stanford team to better understand the opportunity for change (where to play), address shortcomings (how to win), and develop a future focused, integrated model for complex care (what to do).

Where to Play: Why the Patient Experience Was Failing and Where the Opportunity Lies

One hallmark of large, complex healthcare systems is that patients tend to get care in a variety of settings that have little or no connection to each other. That can lead to poor coordination of services. But Stanford sensed their patient experience problem was deeper than that; they needed to understand more broadly what was causing the failure in order to figure out the right solution.

To achieve that goal, Jump led the team on an in-depth research initiative that included everyone within Stanford’s healthcare ecosystem — patients and families, physicians, front-line staff, social workers, case managers, child life specialists, chaplains, and community/home-based service providers.

The analysis revealed several misconceptions. Hospital doctors and specialists often believed they had to do it all themselves. They underestimated families’ abilities to participate in care. They also weren’t thinking beyond the presenting medical issues to consider families’ larger life goals for their children.

By necessity, everyone involved was over-relying on one or two people within a care team to understand everything going on. When those few people weren’t available, a family’s needs were either misunderstood, miscommunicated, or ignored. Families were frustrated and patient experience collapsed.

All of this pointed to the fact that hospitals can’t, nor should they, provide complex care alone. There are many people in these children’s lives who care deeply and want to participate. But sometimes they lack the tools, confidence, and expertise to partner with systems like Stanford.

Solving the problem wasn’t simply a matter of better coordination. The opportunity involved connecting more broadly to family goals, streamlining communications, and engaging the care community beyond Stanford itself.

How to Win? Optimizing Care That Also Controls Costs

It became clear that providing a higher-level patient experience for complex care required delivering that care in an entirely new way — seamlessly across the continuum of inpatient, outpatient, pediatric intensive care, and home. This meant getting everyone on the same page by:

- Working within the context of the patient and family’s entire life

- Fostering trust between departments, ensuring that any individual doctor would not need to be 100% involved in every patient’s care 100% of the time

- Accounting for the many caregivers outside of Stanford Children’s Health system who wanted to and should be involved in a child’s care

This is typically the point in time when many leadership teams look to industry benchmarks or their company’s peers to design a solution. In this case, benchmarking peer organizations wouldn’t have been helpful; no other healthcare systems shared the unique situation of Stanford. Moreover, the limitation of benchmarking within a peer setting is the risk of benchmarking poor performers.

Stanford needed to design its own service delivery model that was collaborative and whole-life focused. It was trying to do something that had never been done before. To do that requires hybrid thinking and collaboration. Jump led a series of co-creation sessions with parents, pediatric patients, physicians, and staff to work through the details. What emerged was a care model built on three pillars: pact-based engagements, flexible delivery teams, and brand ambassadors.

Stanford Children’s Service Delivery Model

Agreements at the onset align everyone involved (patients, families, doctors, and community care providers) on each family’s goals and expectations.

Flexible, team-based care groups reduce the burden on any one individuals within the care team and eliminate a critical point of failure.

Roles within care teams focused on training outside healthcare providers, including in the children’s homes and communities.

What Should We Do? Testing and Scaling the Delivery Model

Less than 18 months after receiving the letter from The Joint Commission, Stanford Children’s Health was ready to put its new service delivery model through its paces. The goal was to learn and refine the model to make it as effective as possible for real patients. This was accomplished through three phases:

Building the right team – Jump defined the capabilities needed to make the program a success, writing the job description for a program director and assisting with interviewing and hiring.

Refining through structured testing and learning – Stanford Children’s Health started with 20 of the most complex patients in its care, including Amy. Each of these patients, their families, and their providers became its own pilot project. Amy’s team included 17 members with representatives from the various specialties she sees, her primary care physician, and home nurses. Amy, who pretty much had her own revolving door at the hospital prior to the program, was hospitalized just once during the pilot and only for a two-day stint. The new model dramatically improved the situation for everyone involved, especially Amy.

Scaling the model – After seeing success in the test and learn phase, Stanford Children’s Health was ready to scale the program to more families. Within two years, the hospital had 100 patients enrolled.

Future Focused- Stanford Children’s Story

Download, save, share

Stanford Establishes the New Standard in Industry-Leading Pediatric Complex Care

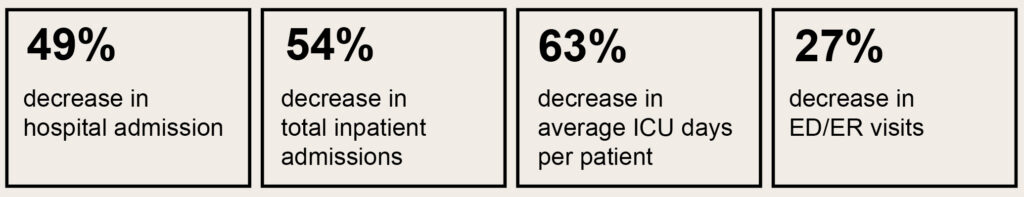

By 2017, more than 700 patients were benefiting from Stanford Children’s new CORE program (Coordinating and Optimizing Resources Effectively). Preliminary data for the most complex group of participants showed outstanding results. The program was achieving its stated goals – improving outcomes, enhancing the patient experience, and reducing costs.

Children’s Hospital Association took note of what was happening, and Stanford Children’s Health became one of the nation’s 10 leading children’s hospitals to partner on the CARE (Coordinating All Resources Effectively) program, a three-year, $23 million landmark national study focused on improving outcomes and reducing the cost of healthcare for children with medical complexity.

Maybe even more important, the program was changing families’ lives for the better. A June 2020 article on the hospital’s website tells the story of Aubry Fair and her mom Kathryn’s experience with the CORE program. Aubry’s mysterious health issues began when she was just 10 months old, and the family soon found itself with a team of specialists. Enrolling in the program and taking advantage of the support of her daughter’s care team has been a “lifesaver” for mom, who has seen her daughter through more than 40 hospital admissions, countless tests, and many illnesses and setbacks. She’s been empowered to the point where she feels she’s not just part of the team — she’s helping to “run the show.”

Lessons From the Field of Complex Care

Sometimes transformation happens in industries by choice, and other times by chance based on external forces. Either way, Stanford’s success illustrates how a company can reframe even the most complex problems, redefine its challenges, and reorganize for increased value through an insights-driven, future focused approach.

Look at the whole ecosystem of stakeholders — Understanding the needs, experiences, and expectations of all stakeholders enables you to assess your current state and see opportunities where others might not. Multi-directional input is essential in building sustainable new ways of working.

Better experience doesn’t always equate to more costs — Sometimes improving the customer experience does not require higher cost of delivery; in fact, sometimes it can reduce the cost of service. Organizations that are struggling with service delivery need to dig to explore the needs of all their stakeholder to build better ways forward.

Understand the limits of benchmarking — Don’t look to peers to solve problems that they’re also struggling to solve. Look outside your industry and go broad; rely on deep insights to find new models that work for your organization. When you lead with a future focused mindset, you can inspire your team to envision solutions they never thought of before.

Give the organization permission to “test and learn” — Even the best ideas need to be tested and iterated. Give your team time to think beyond pilots by running test and learn experiments. Design your experiments to help your team learn from failures, grow as an organization, and scale around your early successes.

*Name changed for privacy

Jump Associates

Jump Associates